Bio

Verna Josephine Dozier was born on October 9, 1917 to Lonna and Lucie Dozier of Washington, D.C. Two years later her younger sister, Lois, completed the family. Her mother was from the Baptist tradition and raised her daughters in the Christian faith. Her father was agnostic and Verna learned early in life how to talk through her beliefs. The family read scripture and Shakespeare together; both were important in her later life. “It was my mother, not my father, who impressed on Lois and me that we were as good as anybody else. It didn’t matter that we were Black and poor, we were just as good as anybody else. That was my mother’s religion.”

Verna attended Howard University and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English in 1937. At Howard, she was drawn to the ideas of the dean of Rankin Chapel, Howard Thurman. She admired how he embraced asking questions about topics like the divinity of Christ. It was not taboo or off limits. “Some people think questions [about the divinity of Jesus] can shake a person’s faith. It can shake a simple faith—and I think a simple faith should be shaken!“ The embrace of inquiry excited her and she asked her father to join in attending chapel. The next year Verna received a Master’s degree from Howard.

After college, Verna taught in racially segregated public schools, then later in integrated public schools. “I was committed to having my students know they were worthy. … I tried to make a haven in that classroom.” Her experience teaching in the classroom greatly affected how she understood the relationship between learning and teaching. Later, she wrote about the responsibility of the student very similar to how she wrote and spoke about the calling of the laity.

In 1950, Dozier joined Gordon Cosby’s church, Church of the Savior in Washington D.C. The model for the church was small groups that did intentional study, prayer, and tithed their income. They met intensively for a few years and then the group would disperse and go into other churches. The goal was to seed the area with Christian educators and leaders in congregations throughout the DC area.

When it was time for Verna to find a church, she was interested in St. Mark’s Capitol Hill. Through church work, she had met the rector, Bill Baxter, who had told her that the all-white church was ready to racially integrate. When Verna asked to join the church, the vestry interviewed her about why she wanted to join. Dozier wrote about her prior experience with Episcopalians: “My classmates … who were Episcopalian always had the fairest skin. They were always the ones whose parents had gone to college and whose parents didn’t have laboring jobs. Episcopalians were always a more privileged group and they just seemed a world apart from me—I never dreamed of associating with those people.”

Eventually, St. Mark’s embraced Verna. She was the first female senior warden, serving from 1971 to 1973. On June 9, 1979, the central altar was dedicated in honor of her and another former senior warden, Bruce Sladen. In 1999, a window was dedicated to Dozier, centering on the theme of Amos, one of her favorite books of the Bible. She and her sister Lois are depicted in the window. In 2017, 11 years after her death, St. Mark’s celebrated her centennial birthday and dedicated a painting of Verna Dozier by parishioner Tracy Council.

After more than thirty years of service, Verna retired from teaching and pursued work in the church full-time. “When I began my second career, people would say, ‘You taught school for thirty-two years; then you began your ministry.’ In my unredeemed way, I would steel myself and reply through clenched teeth, ‘No, I continued my ministry.’” The ministry of the laity was an important theme for Verna. She believed that of clergy and laity, the laity had the harder job since they needed to be well versed in theology and scripture as well as their chosen vocation.

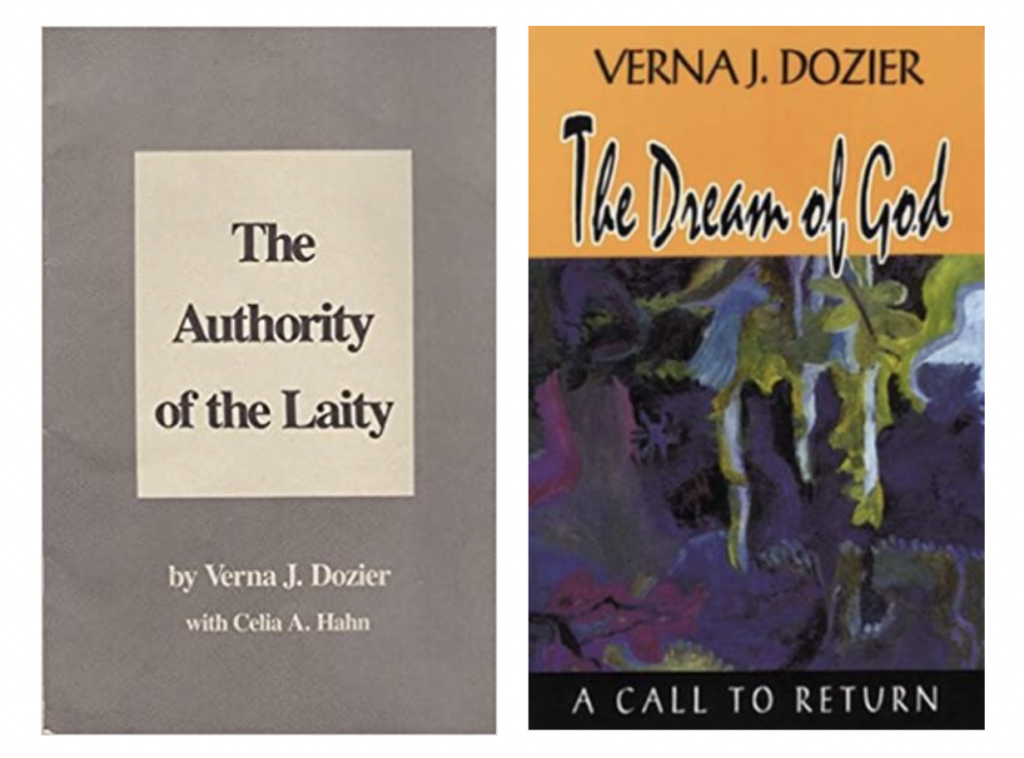

Verna published several books, including The Authority of the Laity (1982) and The Dream of God (1991). She saw herself as a radical. “I probably am one of the most radical voices in this church today but people respond to me with great affection and love because I look like Aunt Jemima.” After the exposure to Shakespeare as a child, Verna saw herself as an orator. She used rhetoric and fiery language to shake people out of complacency.

Verna’s central teachings were about the distinction between the church as the people of God and the church as an institution. She believed lay Christians had the same responsibility as ordained Christians to devote time to rigorous study of the Bible. “The separation of the body into clergy and laity was not intrinsically sinful. … The sin lay in what we did with the division, assigning to one part the designation that belonged to the whole people of God—holiness. Baptism was no longer all that was necessary to identify the chosen. We had to pile on ordinations and consecrations.” Verna believed that baptism was the entry into ministry.

Verna was devoted to intense biblical study. She had her own method of Bible study and led conferences and retreats on the overarching story of the Bible. She thought the Bible should only be read in big chunks, enough to understand its place in the arc. She believed in wrestling with the text. “Because the Bible is a theological book, it is a book of wrestlings, not a book of answers.” A central theme in Verna’s work is not looking to the bible for easy answers of quick fixes.

In her later years, Verna Dozier pursued writing on the subject of ambiguity. She was critiquing a culture that wanted easy answers and wanted them now. “We resist living with the doubt, incompleteness, confusion and ambiguity that are inescapable parts of life we are called to live. Living by faith means living in unsureness.” For Verna, embracing ambiguity was part of a faithful life.

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry was a friend of Verna and they share similar ideas. Upon her death in 2006, he wrote, “Verna Dozier has been a mentor and a teacher who has challenged me and encouraged me to dare deeper dimensions of a discipleship formed by faith, grounded in the gospel and lived in daily life in the world.”